Last night, I finally watched the first few episodes of Aaron Sorkin’s “The Newsroom,” and something struck me about the first episode: All of the on-shift newsroom staffers are sitting around, working at their computers, and a story comes on the AP wire, which turns out to be the explosion at BP’s Deepwater Horizon well in the gulf of Mexico. The date is April 20, 2010. The rest, as they say, is history. What’s interesting though is that the camera gives us several closeup shots of the screen, and it basically looks a lot like an email inbox: each new story pops up on a vertically arranged list, probably arranged in chronological order. To make things easier or journalists, each story is tagged with a different color, yellow, orange and red indicating increasing levels of urgency and relevance. (Probably something along the lines of AP ENPS.) Now, don’t get me wrong: It’s a good system. It’s simple, it’s clear and it works. But being in the business of making things work better, something struck me about the limitations of that design: All it is is a whistle, a bell. Integrated into some basic productivity applications, sure, but my immediate reaction was to ask “what… that’s it? Where’s the rest of the info?”

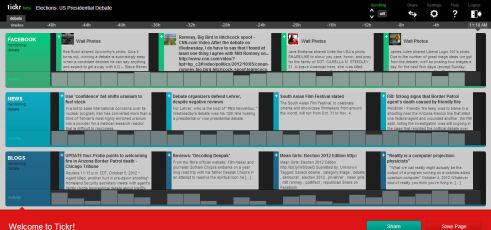

The rest, of course, being something like this:

Remember that what we are talking about is a newsroom, which is to say the central nervous system of a news network. This is where almost 100% of the discovery, fact-finding, research, phone interviews and analysis take place. This is where questions are asked and answered, and where invariably, if journalists are doing their jobs properly, pertinent questions are quickly replaced by difficult ones.

Every story begins with simple facts: What happened? Where did it happen? When did it happen? Who was there? How did it happen? What were the immediate consequences? What is the situation like now?

As a story develops, the questions begin to change: What will the situation be in twenty minutes, an hour, twelve hours, etc.? Why did this happen? Who is responsible? What is the timeline? What are the ramifications of this event?

News stories are living, breathing things. As they evolve so do the angles from which we understand and analyze them. Now… sometimes, a story is just a story: Something happens, it gets reported, people react, the news cycle rolls on. But sometimes, a story doesn’t just come and go. Some stories stick around. The explosion at BP’s Deepwater Horizon didn’t end when the survivors were evacuated and the well sank into the Gulf of Mexico. The story changed. It evolved. On April 20th, we were talking about an explosion on an oil well. On April 21st, we were talking about Halliburton and cement. On April 22nd, we were talking about one of the worst man-made environmental disasters in history. On April 23rd, we were talking about the Minerals Management Service and the impact of inadequate federal funding on offshore platform safety inspections. In May, we were talking about BP CEO – Tony Hayward.

Some stories stick around for a long time. And those stories have long-lasting repercussions we can neither completely anticipate or understand until months later, when we look back on them and understand their timeline against the greater context of how the world changed as a result of an event that just started as a yellow, orange or red item on a news wire feed. Think of the financial collapse. Think of the Arab Spring. Think of the the raid on Osama Bin Laden’s secret compound in Pakistan. These stories are still alive. Each of them has already sprouted thousands of follow-up events, all stories in their own right. Some of them have become major news items of their own. From the latest US Presidential election to the violence in Egypt, Libya and Syria, these stories are still developing.

So here I was, watching that little screen in “The newsroom” with its black on white, email-looking design, wondering “is this how news organizations still monitor what’s going on?” It felt archaic, out of date, terribly limited. Coming from a multi-screen culture, one in which digital mission control centers are quickly becoming the norm, it was shocking to me to see journalists still discovering stories the same way they had for generations. The devices may have changed over the last few decades, there may be screens instead of paper now, but what I saw was still the old “wire,” the old telex, the old fax. Prettier, sure – the story pops up on a flat screen now – but the process is still the same as it was when stories were telegraphed from some Western Union office in the middle of nowhere to New York or London or Paris. It hasn’t improved a whole lot. It worried me, even, to learn that they might be so disconnected from the real-time world of developing stories.

From the digital command centers used by NASA and military commanders in the field to the ones used by brands like PepsiCo (client), Dell and Edelman Digital, I have come to expect banks of screens feeding data into intuitive graphics. I have come to expect information from a plethora of sources telling different facets of a same story on adjacent screens. As an information junkie, and being in the business of deriving insights from business intelligence, I have come to expect an orgy of data. And the thing is, it isn’t hard to do this. The tools exist now. They’re out there, dozens of them. Hundreds, even. It isn’t that difficult to build a modern, intuitive monitoring center for a newsroom that can quickly give journalists not just a sense of what is going on in the world but will also give them a better field view of how a particular story is unfolding over time.

Have you ever wondered how it is that when an earthquake hits Tokyo, you know about it via Twitter, Facebook or Instagram a full 40 minutes before you will hear about it on CNN or the BBC? It isn’t just that professional news organizations need time to confirm stories with reliable sources. Their discovery process for news stories may also need an upgrade.

There’s a new breed of journalist out there doing amazing things with social media. One of them is NPR’s Andy Carvin (@acarvin on Twitter. I recommend that you follow his feed so you can see him in action). I first noticed him during the “Arab Spring.” His coverage on Twitter was better than all of the news organizations’ coverage combined. Why? Two reasons:

1. He was able to point his audience to live updates from eye-witnesses and participants. Citizen journalists, if you will. The raw, unfiltered tweets, photos and videos of people in the middle of the story sharing what they were experiencing, using only their cell phones.

2. He was able to verify his sources in minutes. Part of it was instinct, part of it was validation from other trusted sources, but it worked. When foreign government agents tried to feed him false information, he was able to spot the subterfuge immediately.

What Andy Carvin did with social media, his style of reporting, was one of the most exciting things I have seen in journalism in a long time. It was fast, it was fresh, it was effective and professional. But more than anything, it was bold and clever, and no one else out there was doing it. This is a guy who wasn’t just relying on the AP wire to find out about a story. He understood that by monitoring social channels, which is to say real-time, first person publishing channels, he could find himself in the middle of a news story anywhere in the world and report on what was going on there more clearly and effectively than if he was there himself.

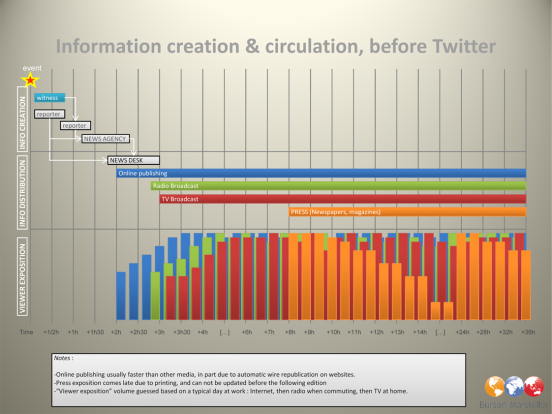

I want to show you something. Below are two graphics. The first shows you the speed of news before Twitter. The second shows the speed of news after (since) Twitter. It will help put the changes taking place in the news business in perspective. Pay particular attention to the left side of the graphic.

Do you think that in five years, the world’s most trusted news rooms around the world will still be relying on a color-coded news wire to discover unfolding news? Do you think that they will be operating without a real-time, multi-channel information control center? If so, think again. Technology will never take the place of solid journalism. It will never replace good instincts, thorough investigative work and the responsible, professional reporting of facts. But technology is already changing the speed, depth and breadth of discovery, research, reporting and analysis. Before long, monitoring control centers will be standard in newsrooms, and that is a very good thing.

On a side-note, though the focus of our upcoming release (the details of which are still super double-top secret for now) is brand management and monitoring, it occurs to me that the applications for news organizations are… well, it could be a bit of a game-changer. I can’t wait to be able to show you what’s coming. You’ll get it as soon as you see it.

Soon. Soon.

Until then, even if you aren’t a journalist, check out Tickr’s free trial version. Use it as a keyword search tool. Use it to follow a story or topic. Get familiar with how it works and how easy it is to use. From news and chatter about the US Presidential debates to the latest PR crisis, you’ll get an appreciation for how powerful this kind of monitoring overwatch app is, as well as how much it already simplifies discovery and monitoring. I think you’ll like it.

Check out all that Tickr has to offer.

Subscribe to our news feed on Facebook.